Last edited by @Adler 2025-01-09T10:36:31Z

花甲和古稀是咋判断出来的,万一文章里说的就是70岁呢(

确实,十大流行语就是一些狗屁不通的玩意

“花甲”误为“古稀”

乒乓名将倪夏莲长期活跃于世界乒坛,深受球迷喜爱。她1963年出生,2024年六十一岁。有报道称倪夏莲“年逾古稀”“步入古稀之年”。其实,年过六十,是年过“花甲”,而非年过“古稀”。古代用干支纪年,以天干与地支依次错综搭配,六十年周而复始,称“花甲”,后用以指人六十岁。“古稀"指人七十岁,语本杜甫《曲江》诗:“酒债寻常行处有,人生七十古来稀。”

转自《咬文嚼字》

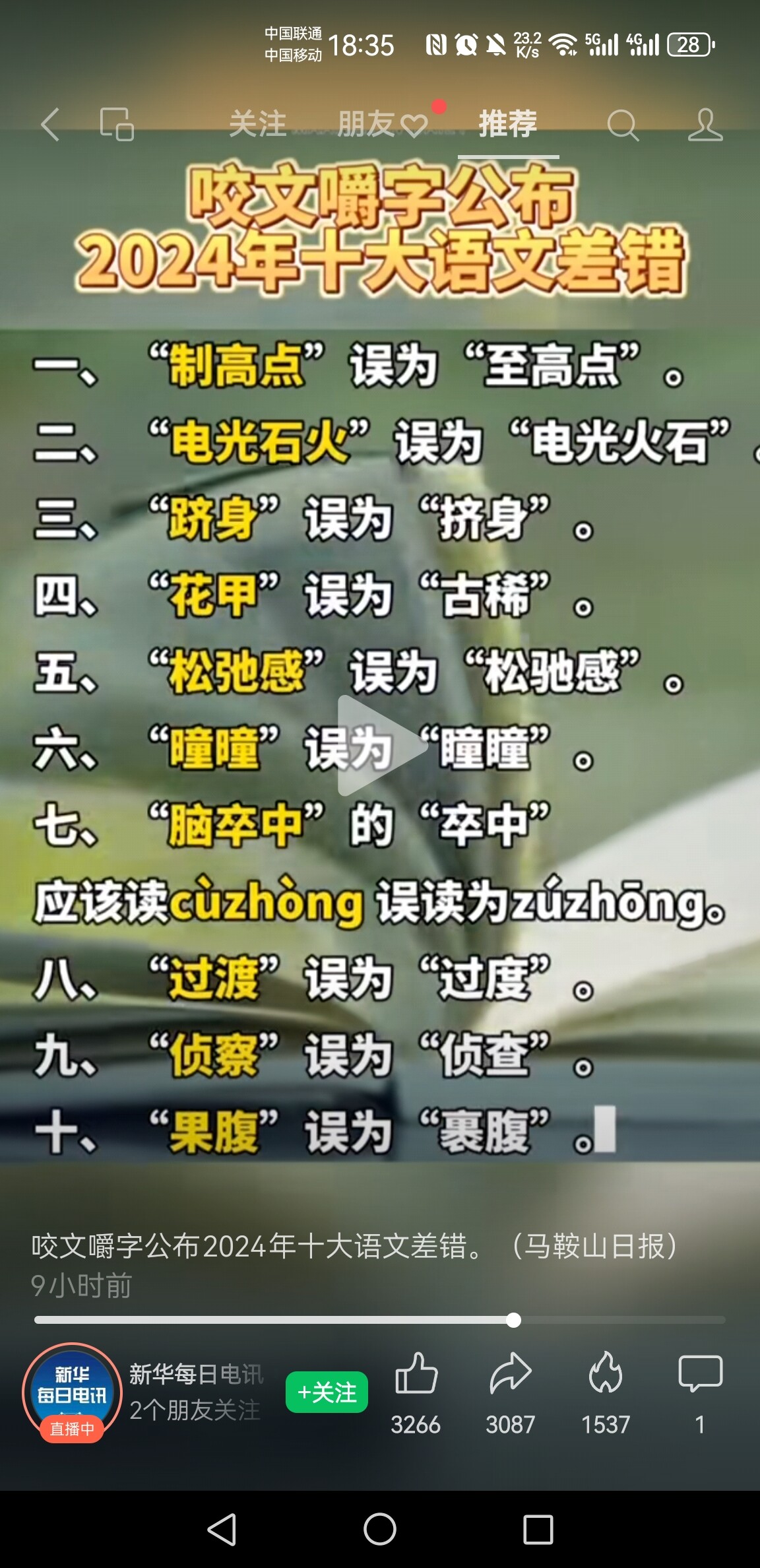

《咬文嚼字》编辑部发布“2024年十大语文差错”

咬文嚼字编辑部 [咬文嚼字](javascript:void(0)![]() 2025年01月07日 16:14 上海

2025年01月07日 16:14 上海

1

“制高点”

误为 “至高点”

人工智能技术突飞猛进,科技巨头纷纷抢占行业制高点。不少报道把“制高点”误写成“至高点”。“至”有“最”的意思,“至高点”即“最高点”。而“制高点”本是军事用语,指能够俯视、控制周围地面的高地或建筑物等。其中“制”指压制、控制,“制高点”指能获得控制权的高点。抢占“制高点”,不仅要占据某一特定空间的最高点,而且要利用这一优势,获得控制权、拥有掌控力。“制高点”误为“至高点”,化优势为胜势的意思荡然无存。

2

“电光石火”

误为 “电光火石”

在巴黎奥运会上,中国体育健儿斗志昂扬,奋勇拼搏,其激烈比赛的精彩瞬间常被媒体称为“电光火石”,这个词正确的说法应该是“电光石火”。“电光”指闪电之光,“石火”指击石之火,“电光石火”常用来形容转瞬即逝的事物,也形容极快的速度。“火石”是燧石的俗称,两块燧石擦击,可以取火。闪电之光,稍纵即逝;取火之石,固态坚实。“电光”与“火石”形态相去甚远,并举使用不当。

3

“跻身”

误为 “挤身”

网球新星郑钦文在2024年大放异彩,屡获佳绩,跻身国际女子网球协会(WTA)年终总决赛。有报道把“跻身”误为“挤身”。提手旁的“挤”,本指推开,引申指紧紧靠在一起,如“拥挤”“挤压”等。足字旁的“跻”(jī),本指登上、上升,引申指晋升,如“跻升”即指升迁。郑钦文通过获得优异成绩而得以置身世界女子网坛前列,应该用“跻身”,因为这是社会地位的提高,与拥挤无关,不能写成“挤身”。

4

“花甲”

误为 “古稀”

乒乓名将倪夏莲长期活跃于世界乒坛,深受球迷喜爱。她1963年出生,2024年六十一岁。有报道称倪夏莲“年逾古稀”“步入古稀之年”。其实,年过六十,是年过“花甲”,而非年过“古稀”。古代用干支纪年,以天干与地支依次错综搭配,六十年周而复始,称“花甲”,后用以指人六十岁。“古稀”指人七十岁,语本杜甫《曲江》诗:“酒债寻常行处有,人生七十古来稀。”

5

“松弛感”

误为 “松驰感”

2024年,“松弛感”一词广为流传。遗憾的是,常有人把“松弛感”误写成“松驰感”。马字旁的“驰”,本指使劲赶马,引申指车马等跑得快,又泛指快跑、疾行,如“驰援”。弓字旁的“弛”,本指放松弓弦,含义与“张”(本指上紧弓弦)相对。引申指放松、松懈,如“弛缓”,又指解除、废除,如“弛禁”。“松弛”可指放松、不紧张,也可指松懈、不严格。如今“松弛感”多用于指面对压力时淡定从容、不慌张、不焦虑的心理状态。“松弛”无关驱驰,“松弛感”不能写作“松驰感”。

6

“曈曈”

误为 “瞳瞳”

“千门万户曈曈日,总把新桃换旧符”,这个诗句反复出现于辞旧迎新的春节期间,其中的“曈曈”常被误写。2024年央视春晚播放西安分会场节目,字幕就把“曈曈”误成了“瞳瞳”。目字旁的“瞳”,本指瞳孔,即眼球虹膜中心的圆孔,后也借指目光。日字旁的“曈”,含义与太阳有关,叠用作“曈曈”,形容太阳刚升起时明亮的样子。“千门万户曈曈日,总把新桃换旧符”出自王安石《元日》,描写的是新年到来、万象更新的美好景象,其中的“曈曈”不能写成“瞳瞳”。

7

“脑卒中”的“卒中”

误读为 zúzhōnɡ

近年来,全国各地医院稳步推进“脑卒中”防治工作。遗憾的是,“卒中”常被误读为zúzhōnɡ。“脑卒中”简称“卒中”,俗称“中(zhònɡ)风”。这是由脑血管突发破裂或阻塞引起的脑组织损伤,是一种高发病率、高死亡率、高致残率的急性疾病。“中风”是中医学说法:“中”指被侵袭、被伤害,另如“中伤”;“风”则指急症,另如“痛风”。“卒”读zú,泛指士兵,还指终止、完毕;读cù,义为突然,后多作“猝”。“卒中”即突然被侵袭,应该读cùzhònɡ。读成zúzhōnɡ,表达不出突然被伤害的意思。

8

“过渡”

误为 “过度”

2024年,美国大选特朗普获胜,韩国总统尹锡悦被弹劾,叙利亚巴沙尔政权崩溃,诸多权力更迭中往往有一个过渡,“过渡政府”等词频现各类媒体中。但不少报道把“过渡”误写成“过度”。“度”本指计量长短的标准,引申指程度、限度。“过度”指超过适当的限度,如“过度疲劳”“过度兴奋”。三点水的“渡”,本指横过水面。“过渡”字面义即横越江河,后引申指事物由一个阶段逐渐发展而转入另一个阶段,如“过渡时期”“过渡地带”。“过渡”与“过度”,音同形近,含义迥别。“过渡政府”等中的“过渡”不能写作“过度”。

9

“侦察”

误为 “侦查”

2024年,巴以冲突持续升级,俄乌前线战事胶着,无人机频频现身相关报道。不少媒体将“侦察无人机”误作“侦查无人机”。“侦查”是法律用语,指公安机关、国家安全机关和检察机关在刑事案件中,为了确定犯罪事实和证实犯罪嫌疑人、被告人确实有罪而进行调查及采取有关的强制措施,如“侦查案情”。而“侦察”是军事用语,指为了弄清敌情、地形及其他有关作战的情况而进行活动。“侦察无人机”在空中侦察战况,执行的是军事任务,不能写作“侦查无人机”。

10

“果腹”

误为 “裹腹”

巴以冲突愈演愈烈,人道主义灾难前所未有,加沙地带民不聊生。有媒体报道称:“大量加沙民众只能挖野菜裹腹”,“加沙民众食不裹腹”。其中“裹腹”是“果腹”之误。“果腹”出自《庄子·逍遥游》:“适莽苍者,三餐而反,腹犹果然。”“果”本指果实,“腹犹果然”形容肚子像果实一样饱满,后以“果腹”指吃饱肚子。“裹”可指缠绕、包扎,如“包裹”,还可指夹杂,如“裹挟”。“果腹”不能写作“裹腹”。

@Creative 分析上述說法是否有誤

Here’s a thinking process to analyze the user’s question:

-

Identify the core question: The user is asking about the validity of the “Huajia” (花甲) and “Guxi” (古稀) distinction made in the article and whether it’s possible the original article meant 70 years old despite using “Huajia.” They also express a general negative opinion about the “Top Ten Misused Words” list.

-

Break down the question into parts:

- Validity of “Huajia” vs. “Guxi” distinction.

- Possibility of the original author meaning 70 despite saying 60.

- User’s opinion on the “Top Ten Misused Words.”

-

Address the “Huajia” vs. “Guxi” distinction: The article provides a clear explanation of the difference, citing the origin and meaning of each term. “Huajia” literally means “flower cycle” and refers to the 60-year cycle in the traditional Chinese calendar, thus representing 60 years of age. “Guxi” comes from a poem and means “rare in ancient times,” referring to the age of 70. The article emphasizes the mistake of using “Guxi” for someone 60 years old.

-

Address the possibility of the original author meaning 70: While it’s possible the original author made a mistake and meant 70, the article correctly points out the error in the wording. The focus is on linguistic accuracy. The user’s doubt highlights a potential real-world scenario where intent and actual wording diverge. Acknowledge this possibility but reinforce the article’s correctness in identifying the misuse of language.

-

Address the user’s opinion on the “Top Ten Misused Words”: The user calls the list “nonsense.” This is subjective. Acknowledge their opinion but shift the focus back to the objective analysis of the specific point they raised about “Huajia” and “Guxi.” Avoid directly agreeing or disagreeing with the user’s broader statement about the list.

-

Synthesize the analysis: Combine the points into a coherent answer. Start by confirming the article’s accuracy on the “Huajia”/“Guxi” distinction. Then address the user’s point about the possibility of the author meaning 70, explaining why the article still correctly identifies a language error. Finally, acknowledge the user’s general opinion while keeping the focus on the specific linguistic issue.

-

Refine the language: Use clear and concise language. Avoid jargon. Use phrases like “the article is correct in pointing out…” and “it’s important to distinguish…” to guide the user.

-

Pre-computation/Pre-analysis (Internal): Before formulating the answer, internally process the definitions and explanations given in the text. Understand the etymology and usage of “Huajia” and “Guxi.” Recognize the article’s purpose is to highlight common linguistic errors. Consider the user’s perspective and their valid point about potential authorial intent versus actual wording.

By following this thinking process, we arrive at an answer that addresses all parts of the user’s question accurately and respectfully.你提出的问题很好,指出了“咬文嚼字”这篇文章的一个潜在局限性,以及表达了对“十大流行语”的看法。我们来具体分析一下:

关于花甲和古稀的判断:

- “咬文嚼字”的逻辑是对的: 从语言规范的角度来说,文章解释了“花甲”和“古稀”的明确含义和来源。“花甲”特指六十岁,而“古稀”特指七十岁。因此,当报道中出现“年逾古稀”来形容61岁的人时,从字面意义上来说是错误的。

- 你提出的疑问是合理的: 你质疑的是文章判断的依据。 确实存在以下可能性:

- 笔误或信息错误: 报道的作者可能原本想说70岁,但误写成了“年逾古稀”,或者接收到的信息有误。

- 模糊表达: 虽然“古稀”通常指70岁,但在某些语境下,可能有人用它来泛指年纪较大,尤其是六十多岁的人,虽然这种用法并不规范。

- “咬文嚼字”的侧重点: 《咬文嚼字》这类刊物的宗旨在于规范语言使用,纠正常见的语言差错。 他们的出发点是语言的精准性,而非推测作者的真实意图。 所以,即使存在你说的可能性,他们依然会指出这种用词是不规范的。

如何判断?

- 上下文和语境分析: 如果你是读者,遇到这种情况,需要结合文章的上下文和其他信息来判断。例如,如果文章中其他地方提到了年龄是61岁,那么“年逾古稀”很可能是一个用词错误。

- 作者的意图: 如果有可能,了解作者的背景和写作习惯也有助于判断。但对于《咬文嚼字》来说,他们通常无法也无需去探究具体作者的意图,而是基于语言的规范性进行判断。

关于“十大流行语”的看法:

你的看法是主观的,但也是很多人共有的感受。 “十大流行语”往往反映了当年的社会现象和公众情绪,但有些词语确实显得空洞、缺乏实际意义,或者很快就被遗忘。

总结:

- “咬文嚼字”关于“花甲”误为“古稀”的判断,从语言规范的角度来看是正确的。

- 你提出的“万一文章里说的就是70岁呢”的疑问是合理的,提醒我们理解语言需要结合语境,但也侧面说明了准确使用语言的重要性,避免产生歧义。

- 你对“十大流行语”的负面评价是个人观点,可以理解。

总的来说,这反映了我们对于语言规范和实际使用之间可能存在的差异的思考。 《咬文嚼字》的作用是提醒我们注意语言的规范性,但这并不意味着我们不需要结合实际语境进行理解和判断。

分析10個詞是否是否真的誤為了

Here’s a thinking process to analyze the validity of the 10 “mistakes”:

-

Understand the Goal: The user wants to know if the ten listed word usages are genuinely mistakes. This requires going beyond simply accepting the article’s claim and examining each case individually.

-

Approach Each Case Systematically: Create a mental checklist for each entry:

- Definition/Meaning of the Correct Term: What does the article say is the right word and why?

- Definition/Meaning of the “Mistake”: What does the article say is the wrong word and why is it wrong?

- Nuance and Context: Are there situations where the “mistake” word could be considered acceptable or have a slightly different but related meaning? Is the article considering all possible contexts?

- Frequency of Misuse: Is the article pointing out a rare error or a genuinely common one? This doesn’t necessarily invalidate the correction, but it provides context.

- Prescriptivism vs. Descriptivism: Is the article taking a strictly prescriptive stance (how language should be) or acknowledging descriptive usage (how language is used)? This is a key point for evaluating validity.

-

Apply the Checklist to Each Entry (with internal thought process examples):

-

1. 制高点 vs. 至高点: The article’s explanation is generally sound. “制高点” has a strategic/control aspect that “至高点” lacks. This feels like a genuine distinction and common error.

-

2. 电光石火 vs. 电光火石: The article’s etymological reasoning is strong. While “电光火石” might be understood colloquially, “电光石火” is the established idiom. This is a clearer case of a recognized idiom.

-

3. 跻身 vs. 挤身: The distinction based on the radicals (foot vs. hand) and meanings (ascend vs. push) is clear and grammatically sound. This feels like a valid correction.

-

4. 花甲 vs. 古稀: As discussed before, the article is correct on the strict definitions. However, acknowledge the user’s point about potential intent. This highlights the prescriptive nature of the article.

-

5. 松弛感 vs. 松驰感: The radical distinction (bow vs. horse) clearly differentiates the meanings. This is a straightforward spelling/character error.

-

6. 曈曈 vs. 瞳瞳: The radical distinction (sun vs. eye) aligns with the meanings (bright sunlight vs. pupil). This is a valid correction based on the specific context of the poem.

-

7. 脑卒中 (cùzhōng) pronunciation: This is a matter of correct pronunciation within medical terminology. The article’s explanation of the etymology of “卒” reinforces the correct reading. This feels like a valid and important correction.

-

8. 过渡 vs. 过度: The radical distinction (water vs. degree) clearly separates the meanings (transition vs. excessive). This is a valid correction.

-

9. 侦察 vs. 侦查: This distinction based on field (military vs. legal) is generally accepted and important for precise language. Valid correction.

-

10. 果腹 vs. 裹腹: The article’s etymological explanation for “果腹” is sound. “裹腹” has a different meaning (wrap the stomach). This is a valid correction.

-

-

Synthesize and Categorize: Group the findings into different categories to provide a nuanced answer:

- Generally Correct: Most of the entries seem to be pointing out genuine linguistic errors or areas of potential confusion.

- Context-Dependent/Prescriptive: The “花甲 vs. 古稀” example is a good case where the article is prescriptively correct but doesn’t fully address nuances of intent.

- Clear Etymological/Grammatical Errors: Many cases rely on distinct meanings based on radicals or established idioms (电光石火, 跻身, 松弛感, 曈曈, 过渡, 果腹).

- Pronunciation: The “脑卒中” example highlights the importance of correct pronunciation, especially in specialized fields.

- Field-Specific Terminology: “侦察 vs. 侦查” is a good example of distinct terms within specific domains.

-

Formulate the Answer: Start with an overall assessment (mostly correct). Then, go through each case, briefly explaining the article’s point and adding any nuances or alternative perspectives. Use cautious language where appropriate (e.g., “generally,” “primarily,” “in most contexts”). Acknowledge the user’s initial skepticism and provide a balanced perspective. Specifically address the “花甲/古稀” point due to the earlier discussion.

-

Review and Refine: Ensure the answer is clear, concise, and addresses the user’s question comprehensively. Avoid overly academic language and focus on providing helpful explanations.“咬文嚼字”编辑部发布的“2024年十大语文差错”总体来说,大部分词语的辨析是站得住脚的,指出的用法错误在大多数情况下是成立的。 他们的目的是为了规范语言使用,提高语言的准确性。

但是,就像你之前提出的关于“花甲”和“古稀”的疑问一样,对于这些“差错”的判断,我们可以从更细致的角度进行分析,看看是否真的“误”了,或者说是否存在一些可以探讨的空间:

以下是对这10个词语“是否真的误了”的分析:

-

“制高点”误为“至高点”: 基本成立。 “制高点”强调的是控制和战略地位,而“至高点”仅仅是最高处。在描述竞争和掌控的语境下,“制高点”更准确。

-

“电光石火”误为“电光火石”: 基本成立。 “电光石火”是固定成语,有明确的典故和用法。“电光火石”虽然字面意思可以理解,但不是规范用法。

-

“跻身”误为“挤身”: 基本成立。 “跻身”指提升地位,进入行列,带有向上提升的意味。“挤身”是拥挤的意思,语境完全不同。

-

“花甲”误为“古稀”: 规范上成立,但语境中可能存在误差或特殊用法。 正如之前的讨论,严格来说是错误的。但需要考虑是否存在笔误或者作者对“古稀”有更广义的理解。

-

“松弛感”误为“松驰感”: 基本成立,属于字形错误。 “弛”是放松的意思,“驰”是奔跑的意思,意义不同。“松弛感”是网络流行语,指的是一种放松、不焦虑的状态。

-

“曈曈”误为“瞳瞳”: 基本成立,属于字形错误。 在描述日出景象时,用“曈曈”是正确的,指阳光明亮。“瞳瞳”指眼珠,用在此处不合语境。

-

“脑卒中”的“卒中”误读为 zúzhōnɡ: 基本成立,属于读音错误。 作为医学术语,“卒中”应该读作 cùzhònɡ。读作 zúzhōnɡ 会造成专业术语的误读。

-

“过渡”误为“过度”: 基本成立,属于词义混淆。 “过渡”指事物发展变化的中间阶段,“过度”指超过适当的限度。两者含义不同,语境也不一样。

-

“侦察”误为“侦查”: 基本成立,属于领域术语混淆。 “侦察”多用于军事领域,指军事上的观察、刺探。“侦查”多用于公安、司法领域,指为了查明犯罪事实进行的调查。

-

“果腹”误为“裹腹”: 基本成立,属于词义混淆。 “果腹”指吃饱肚子,“裹腹”指用东西包缠肚子。两者含义不同。

总结来看:

- 绝大多数情况下,“咬文嚼字”指出的错误是成立的,符合语言规范。 这些错误要么是字形错误,要么是词义混淆,要么是专业术语的误用。

- 少数情况下(如“花甲”误为“古稀”),虽然规范上是错误的,但在特定的语境下,需要考虑是否存在其他可能性,例如笔误或信息错误。 但这并不否认规范用语的重要性。

你的看法(“十大流行语就是一些狗屁不通的玩意”) 代表了一种对部分流行语的观感。 语言是动态发展的,流行语的出现是社会文化现象的反映。 有些人认为它们生动形象,有些人则认为它们缺乏内涵或使用不当。 这属于个人观点,不在“咬文嚼字”讨论的范畴之内。 他们关注的是既有词汇的规范使用。

因此,对于这10个词语是否真的“误了”,我的分析是:大部分是确凿的错误,但在个别情况下需要结合语境进行更细致的判断。 “咬文嚼字”的出发点是规范语言,他们的判断在大多数情况下是合理的。