Last edited by @suen 2024-08-13T10:32:40Z

補充課上不朗讀的理由,用讀書筆記。

Modern reading is a silent, solitary, and rapid activity. Ancient read- ing was usually oral, either aloud, in groups, or individually, in a muffled voice. Reading, like any human activity, has a history.

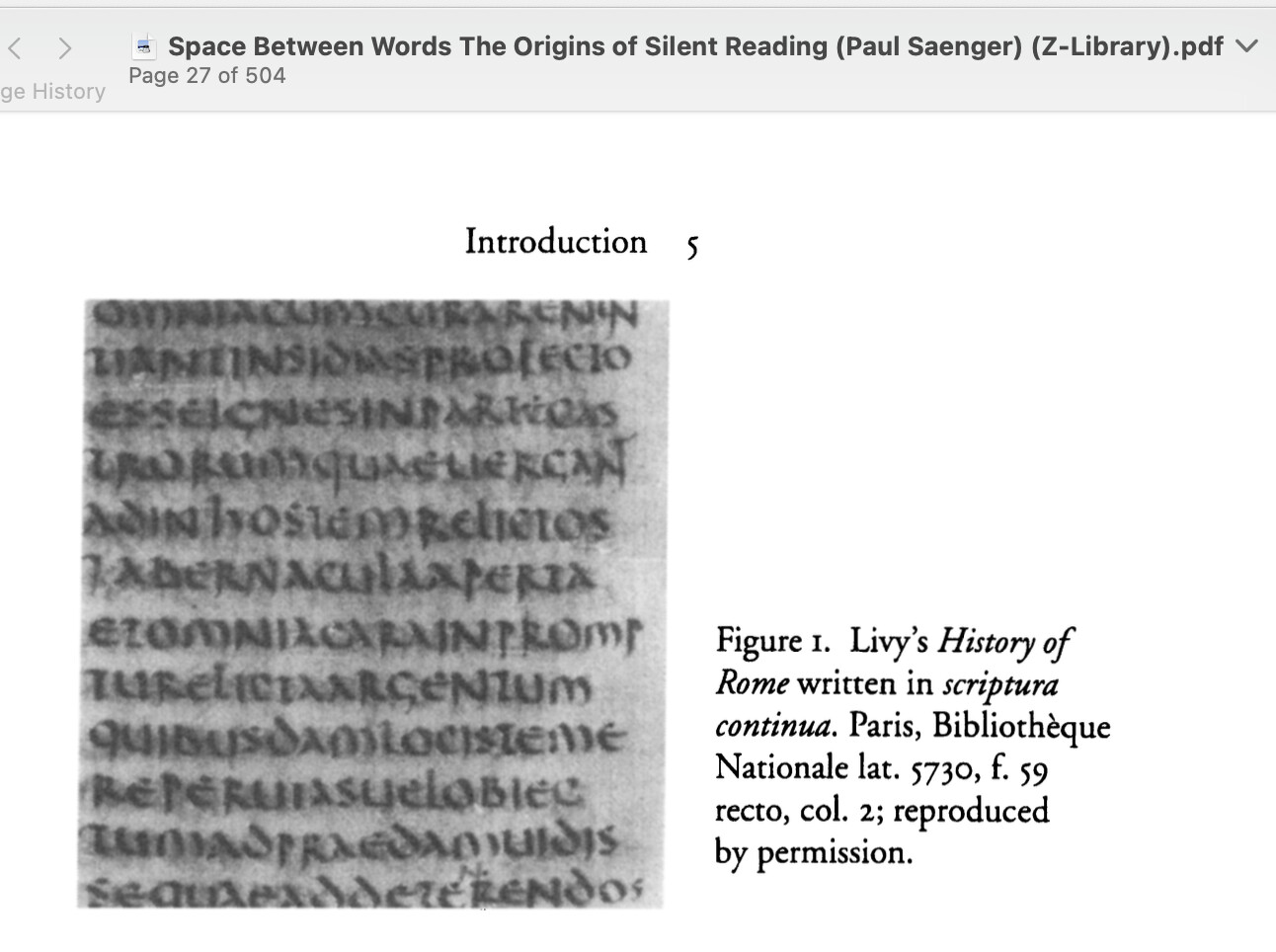

In the West, the ability to read silently and rapidly is a result of the historical evolution of word separation that, beginning in the seventh century, changed the format of the written page, which had to be read orally and slowly in order to be comprehended. The onerous task of keeping the eyes ahead of the voice while accurately reading unseparated script, so familiar to the ancient Greeks and Romans, can be described as a kind of elaborate search pattern.The eye moves across the page,not at an even rate, but in series of fixations and jumps called “sac- cades.” Without spaces to use for guideposts, the ancient reader needed more than twice the normal quantity of fixations and saccades per line of printed text. The reader of unseparated text also required a quantity ofocular regressions for which there is no parallel under modern reading conditions in order to verify that the words have been correctly sepa- rated. The ancient reader’s success in finding a reasonably appropriate meaning in the text acted as the final control that the task ofseparation has been accurately performed.

7世紀前不分詞的手寫,希臘的**無空格書寫(scriptura continua)**此後被廢掉的詞間點的習慣,都硬控著必須出聲讀出來,但此刻,為什麼要出聲?

“The secret history of reading

We tend to think of reading as a largely silent activity. Barring the occasional muffled cough or embarrassed giggle, libraries aren’t traditionally known for being boisterous hubs of activity.For this reason, it might come as a surprise to learn that silent reading wasn’t always in fashion. In fact, until the late seventh century, reading out loud was the most common practice. Far from being havens of peace and quiet, ancient libraries were likely places of clamorous chatter as even solitary readers could be heard mumbling words aloud to themselves.”

“The act of silent reading was so rare in the past that Saint Augustine felt it worthy of mention in his seminal Confessions: ‘When Ambrose read, his eyes ran over the columns of writing and his heart searched out the meaning, but his voice and tongue were at rest. Often … I have seen him reading silently, never in fact otherwise. I ask myself why he read this way?’ This form of writing is called scriptura continua and it demonstrates that reading was largely an oral activity. Of what need are spaces, punctuation or capitalization when text is read aloud? To see what I mean, simply go back and read that last passage out loud: you’ll likely notice that many important aspects of language — things like pacing, inflection and intention — naturally emerge out of your vocalization with little-to-no deliberate effort on your part.

readingaloudwasfacilitatedbythewayancienttextswerewrittenmore specificallyancienttextscontainednospacesbetweenwordsmarksandnocapitallettersinfactifyougotoyourlocallibraryormuseumyou willlikelyfindmanyexamplesofancientgreekandlatinmanuscripts scrawledinthisstyle

If the concept of reading as a vocal activity seems a bit odd or ancient, simply look around: the legacy of this practice is everywhere in modern civilization. University lectures are predicated upon the act of one individual reading aloud important information to a group of listeners (in fact, the French word ‘lecture’ translates to ‘reading’). Church services commonly involve someone reading aloud to the gathered congregation. Scientific conferences, political addresses, even weekly progress meetings are all structured around the ancient practice of individuals reading aloud in public settings.At the turn of the eighth century, Irish monks began adding spaces between words and as this trend spread throughout Europe, so too did the practice of silent reading. So, thanks to a group of ancient monks, you can enjoy the remainder of this book safe in the knowledge that it never need be turned into oral speech …… or does it?It only takes a moment of consideration to realize that the concept of ‘silent’ reading can’t be entirely accurate. If you pull your attention back and focus on what is occurring in your head as you read this sentence, likely the first thing you’ll notice is that you hear something — or, more accurately, someone.Embedded deep within your head there is a voice reading aloud each word as your eyes pass over it. Nine times out of ten you can identify that voice as your own, but this isn’t always the case:‘I ate his liver with a side of fava beans and a nice Chianti.’‘I did not have sexual relations with that woman.’‘That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.”

“If you’re familiar with these phrases, then as you read them there’s a strong chance you heard Hopkins’ chilling precision, Clinton’s confident drawl and Armstrong through a scratchy receiver. It turns out, when we read words strongly associated with a specific person, we hear his or her voice (of course, this only happens when we are reasonably familiar with the person whose words we are reading. I don’t imagine anyone out there, except perhaps my mother, would be hearing my voice right now — hi Mom!).Clearly, silent reading is far from silent; but of what possible importance could this be to the theme of this chapter? To understand why I took you on this whirlwind tour of reading history, we need to briefly shift gears and explore a seemingly unrelated topic.”

Excerpt From

Stop Talking, Start Influencing: 12 Insights From Brain Science to Make Your Message Stick

Jared Cooney Horvath PhD MEd

GPT-4o翻譯:

《閱讀的祕密歷史》

我們通常認為閱讀是一項大多數時候安靜進行的活動。除了偶爾的輕咳或尷尬的竊笑外,圖書館傳統上並不是熱鬧的活動中心。正因如此,了解默讀並非一直流行這件事可能會讓人感到驚訝。事實上,直到七世紀末,大聲朗讀才是最普遍的閱讀方式。古代的圖書館遠非寧靜安詳的避風港,而是充滿喧鬧交談的地方,即使是獨自閱讀的人,也常常會聽到他們低聲朗讀的聲音。「默讀」在過去是如此罕見,以至於聖奧古斯丁在他的重要著作《懺悔錄》中專門提到:「當安布羅修閱讀時,他的眼睛掃過書寫的字列,他的心靈在尋找意義,但他的聲音和舌頭卻是靜止的。經常……我看見他默讀,事實上從未見他以其他方式閱讀。我不禁問自己,他為何如此閱讀?」這種寫作形式被稱為「連續書寫」(scriptura continua),它表明閱讀在很大程度上是一項口語活動。當文本被朗讀時,空格、標點或大小寫的需求何在?要理解我的意思,只需回過頭來大聲朗讀剛才的段落,你可能會注意到語言的許多重要方面——如節奏、語調和意圖——自然而然地隨著你朗讀而浮現出來,幾乎不需要你刻意去思考。

閱讀古代文本是透過連續書寫來促進的更具體地說古代文本中沒有空格標點也沒有大小寫事實上如果你去當地的圖書館或博物館你很可能會發現許多古希臘和拉丁文手稿就是以這種風格書寫的。

如果將閱讀視為一項聲音活動的概念讓你感到古怪或過時,只需環顧四周:這種做法的遺產在現代文明中無處不在。大學講座是以一個人朗讀重要信息給一群聽眾的行為為基礎的(事實上,法語中的「lecture」一詞即為「閱讀」)。教堂禮拜通常包括有人向會眾朗讀。科學會議、政治演講,甚至每週的進度會議,都是圍繞個人在公共場合朗讀的古老做法進行的。在八世紀之交,愛爾蘭僧侶開始在單詞之間加入空格,隨著這一趨勢在整個歐洲傳播,默讀的做法也隨之而來。所以,多虧了古代僧侶,你可以安心享受本書的餘下部分,無需將其轉化為口語……或者是嗎?

只需稍作考慮,你就會意識到「默讀」這個概念並不完全準確。如果你專注於讀這句話時在腦中發生的事情,你可能會首先注意到的是你聽到了某種聲音——更準確地說,是某個人在讀每個單詞。十有八九,你能辨認出那個聲音是你自己的,但這並不總是如此:「我配上一些蠶豆和一杯好酒吃掉了他的肝臟。」(I ate his liver with a side of fava beans and a nice Chianti.)「我沒有與那個女人發生性關係。」(I did not have sexual relations with that woman.)「這是個人的一小步,人類的一大步。」(That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.)

如果你對這些語句熟悉,那麼當你閱讀它們時,很可能聽到了霍普金斯精確的語調、克林頓自信的口音,以及阿姆斯壯通過劃破的接收器傳來的聲音。事實證明,當我們閱讀與某個特定人物密切相關的語句時,我們會聽到他或她的聲音(當然,這只會發生在我們對這個人的語音比較熟悉的情況下。我不認為會有人,除了可能我的母親,在這一刻聽到我的聲音——嗨,媽!)。

顯然,默讀遠非靜默;但這對本章主題有什麼重要意義呢?為了理解我為什麼帶你進行這次閱讀歷史的旋風之旅,我們需要短暫地轉換話題,探討一個看似無關的主題。

這書算是講怎麼講課或不該怎麼講課的,涉及閱讀的章節,比上一層樓給的學術論述輕鬆,一併給。